AMEN INSTITUTE, Parshat Vayechi, Week of December 11-18, 2021

WINDING TOWARD JUSTICE

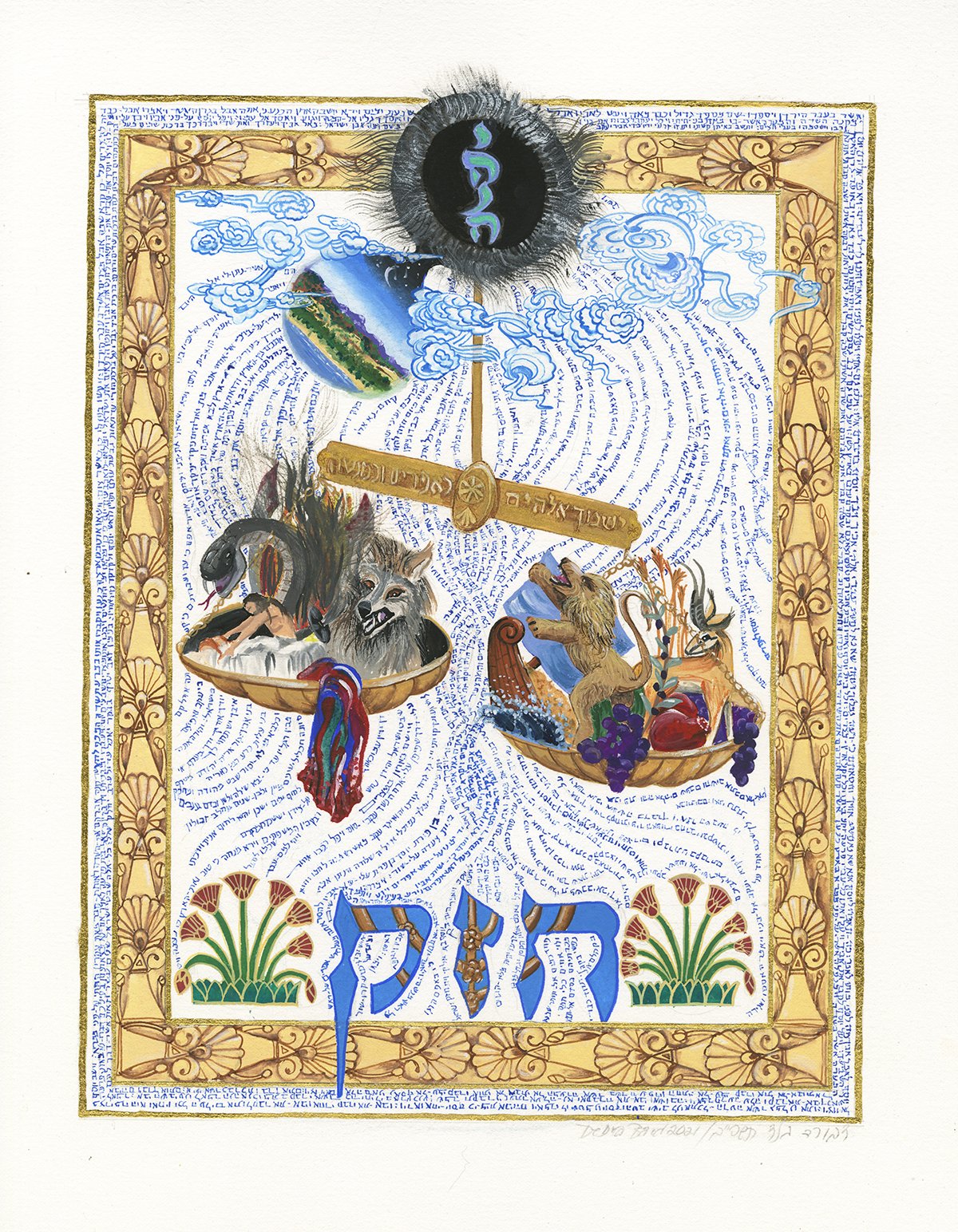

Much of my work—apart from hundreds of ketubot, several illuminated books of biblical texts, each a collaboration with leading scholars—begins with extensive study of academic bible studies and midrash—and for thirty years I’ve been working on building a Jewish visual symbolic vocabulary to express abstract values, with images mostly drawn from midrash. I haunt archeological museums, in particular the Israel Museum and the British Museum, for artifacts of the biblical era, and other periods of Jewish history, that can embody abstract ideas and values raised in biblical text, and many of my works involve symbolism drawn from modern science and across western civilization. In Judaism, visual symbolism of abstract concepts has always tended to be rather thin, largely, I think, because we’ve always had a high degree of literacy, and so didn’t need to learn our religion through pictures and sculpture. However, in this very visual internet era I think visual symbolism has a renewed importance. I’ve brought all of this to bear on this interpretation of Vayechi.

Braishit is a fascinating book—it begins with the creation of ALL matter, and gradually narrows its focus down to one family, and then one man—Joseph—preparing us to burst into the broadening out of our tale with the creation of the nation of Israel –not one family—at the beginning of Shemot. And Vayechi, the turning-point of this motion, is an especially fascinating parshah! To me it is striking that Jacob’s evaluation and prophecy about his sons is offered here—not just his simple love and ambitions for them, but his clear-eyed evaluation of them as men, ranging from the ruthless to the euphoric. The focus on justice particularly strikes me, and indeed this aspect caught the attention of much rabbinic discussion in Braishit Rabbah, the main collection of midrash on Genesis. In this painting, following the lead of midrash, I interpret the parshah’s subtle ideas of justice and judgment, and our ability to correct our course (or not!) following mistakes. Micrography presenting the entire text of Vayechi winds and flows through the painting—one of the most frequent metaphors in all of Tanakh compares Torah to water. The micrographic text begins at top, where we see kabbalistic ideas of G-d’s creation of all matter, hidden from the material world by a firmament of cloud. I’ve encountered these ideas in the writings of the 16th century kabbalist Meir ibn Gabbai; I’m presently working with Art Green and the astrophysicist Howard Smith on a book of ibn Gabbai’s analysis of Creation. Below, where Braishit has narrowed its focus to the story of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, and their relationship with G-d, we see a scale representing Jacob’s keen evaluation of his sons’ characters, their sin and promise—this is the future nation of Israel. The scale’s balance offers the blessing “May you be like Ephraim and Manasseh,” with which parents now bless their sons. The swinging pans hold imagery of the son’s deeds and Jacob’s clear-eyed judgment—sin at left (the Kabbalistic side of G-d’s harder attributes), outweighed by goodness at right (the side of G-d’s gentler attributes). Notably, the Lion of Judah—the tribe that will one day lead all Israel—looks back from the side of good; as Judah remembers his past abuse of his daughter-in-law, Tamar, he has now changed his course so dramatically, done such teshuvah, that dying Jacob knows that this son’s descendants will merit the leadership of all Israel in future. The micrography ends with the word Chazak (be strong), whose painted letters anticipate the Temple’s golden Menorah that Jacob’s distant progeny will one day light. The floral designs flanking the Menorah are an ancient Egyptian motif of papyrus plants, the reeds from which the “paper” of Joseph’s day was made, on which his records would have been written. I mentioned my use of archeological imagery? You can see around the border of the painting a palmette design—this is adapted from a little ivory furniture plaque in the Israel museum that is exactly contemporary with Solomon’s Temple, and was found in the remains of a palace nearby. Palmette designs figure among the decorations described for Solomon’s Temple in Malachim, Kings, and Divrei Hayamim, Chronicles, and although there are hundreds of these patterns around the Mediterranean for two thousand years, there’s strong art historical reasoning to think this particular pattern may be very close to the one used by Solomon’s designers. For many years I have used this motif to allude to the Temple, the ancient focus of divine energy on earth, to which the heritage and value of justice in Parashat Vayechi leads.

Materials used herein include paper, gouache and gold.

The Amen Institute, the creation of Dvir Cahane, hosted a fascinating in-depth discussion of the biblical text, my painting, and the sermon that Rabbi Jason Herman, of the Hudson Yards Synagogue in New York wrote in collaboration with me, about our interpretive and creative processes on December 13, 2021. Enjoy the video!